The problem about being a tourist in the world of endocrinology and molecular biology is that some of the finer points of the science can be beyond us. However, Echo takes great pride in being able to sift through and break down complex concepts, making them accessible to the people who need this information – and when it’s trauma-related that means just about everyone.

One of the things we get excited about is cortisol. Cortisol is one of the cocktail of stress hormones that get released when we are stressed, and in large doses it can be toxic. Hence ‘toxic stress’.

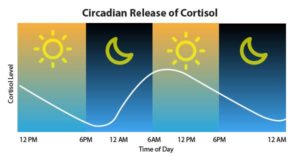

Here’s the funny thing about cortisol – we actually need it to get up in the morning. People with low cortisol walk about all day feeling like a zombie. And at night, we want the cortisol levels to be lower so that we can get to sleep. That’s why exercising right before going to bed, or worrying over some complex situation can have you tossing and turning all night. In addition, as we age, we have higher levels of cortisol and so tend to sleep less.

This makes using cortisol levels as a measure of stress somewhat problematic because they will fluctuate with age, with the time of day… with a host of things.

This makes using cortisol levels as a measure of stress somewhat problematic because they will fluctuate with age, with the time of day… with a host of things.

When we don’t eat our cortisol rises. At first this may help us focus, but then the lack of blood sugar gives us ‘brain fog’. Lack of sleep also increases cortisol – maybe you’ve experienced living on too little sleep for days and then waking up early even when you can sleep in. Jet lag is about us needing to calibrate the diurnal cycles of cortisol to a new time zone. Adults who are lonely or sad have higher cortisol in he morning. This is nature’s way of giving us a boost to deal with overwhelm.

People who have experienced trauma or toxic stress have problems regulating cortisol levels. Instead of the cortisol levels going down after the traumatic event is over, we stay stuck in ‘high alert’ unable to turn off the cortisol production. Partly, this is because the receptors (called ‘glucocorticoid receptors’) in the brain that are supposed to absorb the cortisol and signal the adrenal glands to stop production are themselves damaged by the toxic levels of cortisol. Once this feedback system is broken, it is like revving a parked car – our bodies remain ready for action even when we’re supposed to rest. Hardly surprising that trauma survivors are often highly reactive, startle easily, and live with high levels of anxiety and panic.

At some point, the body is unable to deal with such high levels of cortisol and the adrenal glands power down. (Ever heard of ‘adrenal gland fatigue’?) Now we have the low cortisol, zombie effect, like a car that is idling even when we put it in ‘drive.’ Low cortisol is one of the characteristics of PTSD. Think about the returning vets who complain they no longer find enough stimulation in everyday life and long for the battlefield again just so they can feel something. That friend you have who is always picking a fight? Perhaps they have low cortisol too and need to create drama to feel fully alive. Risky behaviors? Same thing.

Not only do sufferers of long-term trauma have lower cortisol levels but they have also blown out some of their receptors. That means that when something does happen and causes a spike in cortisol, they will get agitated more quickly and take longer to calm down.

For many of us, an accumulation of toxic stress causing spikes in cortisol and damaged receptors is otherwise known as aging. Have a thought for the cranky old person whose system is like a car that has been driven at full speed with the parking break on for years.

What does this all mean? Are we doomed by our lifetime of stress and trauma? Not so. One study showed that older people with elevated cortisol who take health measures, look on the bright side of life, and avoid self-blame will live longer and are resistant to many of the effects of high cortisol, including the onset of Alzheimer’s.

One of the most curious facts about cortisol is that we may transfer cortisol levels and receptor activation to our children. Children of Holocaust survivors have low cortisol just like their parents. Rat pups whose mothers are low nurturers are born with only a few active receptors and will go on to be low nurturers themselves. The good news is that if those rat pups are put with high nurturing mothers, their receptors get activated and they will become high nurturing parents. To paraphrase the eminent epigeneticist, Dr. Rachel Yehuda, who spoke at our conference this March, despite the tantalizing idea that we can measure cortisol levels as an indicator of stress, “it’s not about cortisol levels, it’s all about the receptors!”